Welcome to Andre Norton's Reading Corner

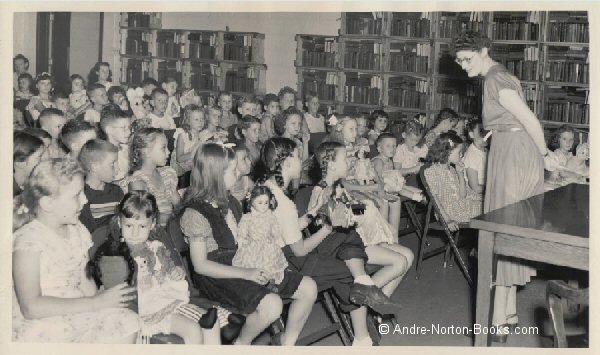

Andre the Librarian hosting "Story Time" at the Cleveland Public Library ~ 1948

"Come on In! . . .Take a Seat! . . . and Settle Down! . . ."

As we share with you a tale by one of the leading story tellers of the past century.

Twice a Month (on the 1st and the 16th) We are going to post an original story by Andre Norton

During the showcase period you will be able to read it here free of charge.

Many were only published once.

So it's a sure thing that there's going to be a few you have never heard of.

The order will be rather random in hopes you return often.

Happy Reading!

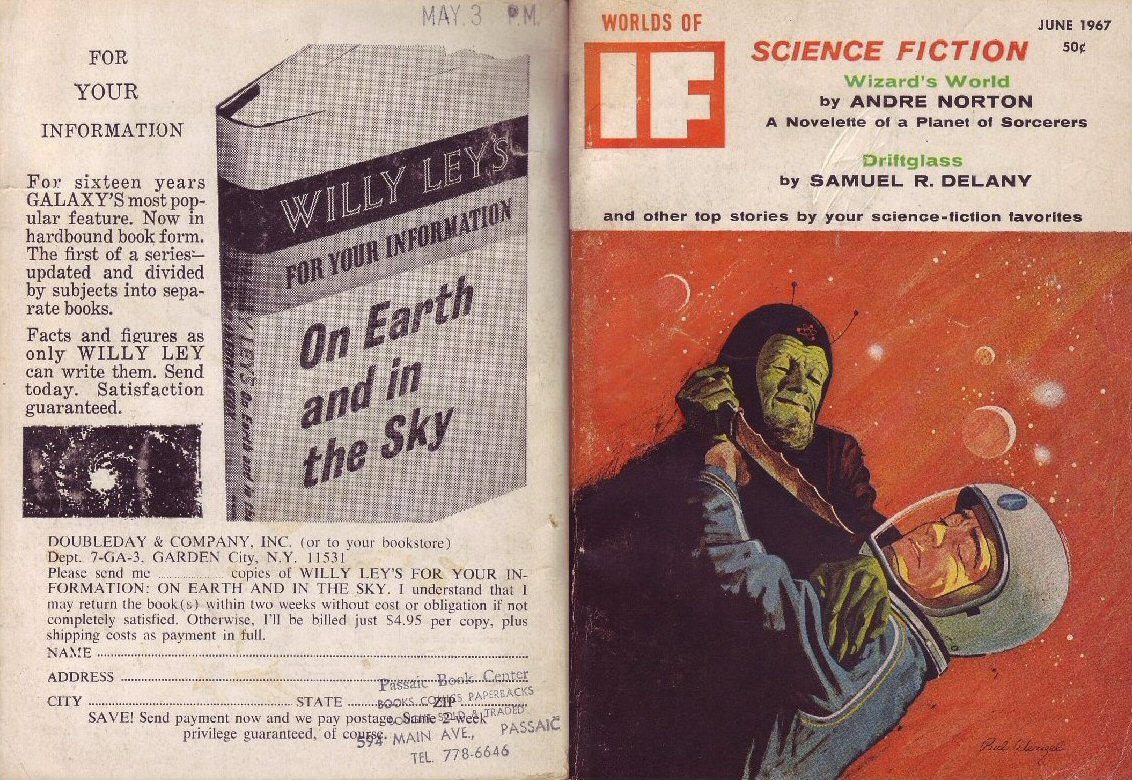

Wizard’s Worlds

A novella by Andre Norton

1st Published ~ Worlds of If (1967) Edited by Frederik Poul, Published by Galaxy Publishing, Mag., $0.50, 164pg, June, (pgs. 7-49) ~ cover by Wenzel

Last Printing in English ~ A Magic-Lover’s Treasury of the Fantastic (1998) Edited by Margaret Weis & Martin H. Greenberg, Published by Warner Aspect, TP, 0-446-67284-X, $13.99, 422pg ~ cover by Keith Birdsong

Bibliography Page - Wizard’s Worlds ~ ss

Chapter 1

Craike’s swollen feet were agony, every breath he drew fought a hot band imprisoning his laboring lungs. He clung weakly to a rough spur of rock in the canyon wall, swayed against it, raking his flesh raw on the stone. That weathered red and yellow rock was no more unyielding than the murderous wills behind him. And the stab of pain in his calves no less than the pain of their purpose in his dazed mind.

He had been on the run so long, ever since he had left the E-Camp. But until last night—no, two nights ago—when he had given himself away at the gas station, he had not known what it was to be actually hunted. The will-to-kill which fanned from those on his trail was so intense it shocked his Esper senses, panicking him completely.

Now he was trapped in wild country, and he was city born. Water—Craike flinched at the thought of water. Espers should control their bodies, that was what he had been taught. But there come times when cravings of the flesh triumph over will.

He winced, and the spur grated against his half-naked breast. They had a "hound" on him right enough. And that brain-twisted Esper slave who fawned and served the mob masters would have no difficulty in trailing him straight to any pocket into which he might crawl. A last remnant of rebellion sent Craike reeling on over the gravel of the long-dried stream bed.

Espers had once been respected for their "wild talents," then tolerated warily. Now they were used under guard for slave labor. And the day was coming soon when the fears of the normals would demand their extermination. They had been trying to prepare against that.

First they had worked openly, petitioning to be included in spaceship crews, to be chosen for colonists on the moon and Mars; then secretly when they realized the norms had no intention of allowing that. Their last hope was flight to the waste spots of the world, those refuse places resulting from the same atomic wars which had brought about the birth of their kind.

Craike had been smuggled out of an eastern E-Camp provided with a cover, sent to explore the ravaged area about the one-time city of Reno. Only he had broken his cover for the protection of a girl, only to learn, too late, she was bait for an Esper trap. He had driven a stolen speeder until the last drop of fuel was gone, and after that he had kept blindly on, running, until now.

The contact with the Esper "hound" was clear; they must almost be in sight behind. Craike paused. They were not going to take him alive, wring from him knowledge of his people, recondition him into another "hound." There was only one way, he should have known that from the first.

His decision had shaken the "hound." Craike bared teeth in a death's-head grin. Now the mob would speed up. But their quarry had already chosen a part of the canyon wall where he might pull his tired and aching body up from one hold to another. He moved deliberately now, knowing that when he had lost hope, he could throw aside the need for haste. He would be able to accomplish his purpose before they brought a gas rifle to bear on him.

At last he stood on a ledge, the sand and gravel some fifty feet below. For a long moment he rested, steadying himself with both hands braced on the stone. The weird beauty of the desert country was a pattern of violent color under the afternoon sun. Craike breathed slowly; he had regained a measure of control. There came shouts as they sighted him.

He leaned forward and, as if he were diving into the river which had once run there, he hurled himself outward to the clean death he sought.

Water, water in his mouth! Dazed, he flailed water until his head broke surface. Instinct took over, and he swam, fought for air. The current of the stream pulled him against a boulder collared with froth, and he arched an arm over it, lifting himself, to stare about in stupified bewilderment.

He was close to one bank of a river. Where the colorful cliff of the canyon had been there now rolled downs thickly covered with green growth. The baking heat of the desert had vanished; there was even a slight chill in the air.

Dumbly Craike left his rock anchorage and paddled ashore, to lie shivering on sand while the sun warmed his battered body. What HAD happened? When he tried to make sense of it, the effort hurt his mind almost as much as had the "hound's" probe.

The Esper Hound! Craike jerked up, old panic stirring. First delicately and then urgently, he cast a thought-seek about him. There was life in plenty. He touched, classified and disregarded the flickers of awareness which mingled in confusion—animals, birds, river dwellers. But nowhere did he meet intelligence approaching his own. A wilderness world without man as far as Esper ability could reach.

Craike relaxed. Something had happened. He was too tired, too drained to speculate as to what. It was enough that he was saved from the death he had sought, that he was HERE instead of THERE.

He got stiffly to his feet. Time was the same, he thought—late afternoon. Shelter, food—he set off along the stream. He found and ate berries spilling from bushes where birds raided before him. Then squatting above a side eddy of the stream, he scooped out a fish, eating the flesh raw.

The land along the river was rising, he could see the beginning of a gorge ahead. Later, when he had climbed those heights, he caught sight through the twilight of the fires. Four of them burning some miles to the southwest, set out in the form of a square!

Craike sent out a thought probe. Yes—men! But an alien touch. This was no hunting mob. And he was drawn to the security of the fires, the camp of men in the dangers of the night. Only, as Esper, he was not one with them but an outlaw. And he dare not risk joining them.

He retraced his path to the river and holed up in a hollow not large enough to be termed a cave. Automatically he probed again for danger. Found nothing, but animal life. He slept at last, drugged by exhaustion of mind and body.

The sky was gray when he roused, swung cramped arms, stretched. Craike had awakened with the need to know more of that camp. He climbed once again to the vantage point, shut his eyes to the early morning and sent out a seeking.

A camp of men far from home. But they were not hunters. Merchants—traders! Craike located one mind among the rest, read in it the details of a bargain to come. Merchants from another country, a caravan. But a sense of separation grew stronger as the fugitive Esper sorted out thought streams, absorbed scraps of knowledge thirstily. A herd of burden-bearing animals, nowhere any indication of machines. He sucked in a deep breath—he was—he was in another world!

Merchants traversing a wilderness—a wilderness? Though he had been driven into desert the day before, the land through which he had earlier fled could not be termed a wilderness. It was overpopulated because there were too many war-poisoned areas where mankind could not live.

But from these strangers he gained a concept of vast, barren territory broken only by small, sparse, strips of cultivation. Craike hurried. They were breaking camp. And the impression of an unpeopled land they had given him made him want, to trail the caravan.

There was trouble! An attack—the caravan animals stampeded. Craike received a startlingly vivid mind picture of a hissing, lizard thing he could not identify. But it was danger on four scaled feet. He winced at the fear in those minds ahead. There was a vigor of mental broadcast in these men which amazed him. Now, the lizard thing had been killed. But the pack animals were scattered. It would take hours to find them. The exasperation of the master trader was as strong to Craike as if he stood before the man and heard his outburst of complaint.

The Esper smiled slowly. Here—handed to him by Fate—was his chance to gain the good will of the travelers. Breaking contact with the men, Craike cast around probe webs, as a fisher might cast a net. One panic-crazed animal and then another—he touched minds, soothed, brought to bear his training. Within moments he heard the dull thud of hooves on the mossy ground, no longer pounding in a wild gallop. A shaggy mount, neither pony nor horse of his knowledge, but like in ways of each, its dull hide marked with a black stripe running from the root of shaggy mane to the base of its tail, came toward him, nickered questionly. And then fell behind Craike, to be joined by another and another, as the Esper walked on—until he led the full train of runaways.

He met the first of the caravan men within a quarter of a mile and savored the fellow's astonishment at the sight. Yet, after the first surprise the man did not appear too amazed. He was short, dark of skin, a black beard of wiry, tightly curled hair clipped to a point thrusting out from his chin. Leggings covered his limbs, and he wore a sleeveless jerkin laced with thongs. This was belted by a broad strap gaudy with painted designs, from which hung a cross-hilted sword and a knife almost as long. A peaked cap of silky white fur was drawn far down so that a front flap shaded his eyes, and another, longer strip brushed his shoulders.

"Many thanks, Man of Power—" The words he spoke were in a clicking tongue, but Craike read their meaning mind to mind.

Then, as if puzzled on his closer examination of the Esper, the stranger frowned, his indecision slowly turning hostile.

"Outlaw! Begone, horned one!" The trader made a queer gesture with two fingers. "We pass free from your spells—"

"Be not so quick to pass judgment, Alfric—"

The newcomer was the Master Trader. As his man, he wore leather, but there was a gemmed clasp on his belt. His sword and knife hilt were of precious metal, as was a badge fastened to the fore of his yellow and black fur head gear.

"This one is no local outlaw." The Master stood, feet apart, studying the fugitive Esper as if he were a burden pony offered as a bargain. "Would such use his power for our aid? If he is a horned one—he is unlike any I have seen."

"I am not what you think—" Craike said slowly, fitting his tongue to the others' alien speech.

The Master Trader nodded. "That is true. And you intend us no harm; does not the sun-stone so testify?" His hand went to the badge on his cap. "In this one is no evil, Alfric, rather does he come to us in aid. Have I not spoken the truth to you, stranger from the wastes?"

Craike broadcast good will as strongly as he could. And they must have been somewhat influenced by that.

"I feel—he DOES have the power!" Alfric burst forth.

"He has power," the Master corrected him. "But has he striven to possess our minds as he could do? We are still our own men. No—this is no renegade Black Hood. Come!"

He beckoned to Craike, and the Esper, the animals still behind him, followed on into the camp where the rest of the men seized upon the ponies to adjust their packs.

The Master filled a bowl from the contents of a three-legged pot set in the coals of a dying fire. Craike gulped an excellent and filling stew. When he had done, the Master indicated himself.

"I am Kaluf of the Children of Noe, a far trader and trail master. Is it your will, Man of Power, to travel this road with us?"

Craike nodded. This might all be a wild dream. But he was willing to see it to its end. A day with the caravan, the chance to gather more information from the men here, should give him some inkling as to what had happened to him and where he now was.

Chapter 2

Craike’s day with the traders became two and then three. Esper talents were accepted by this company matter-of-factly, even asked in aid. And from the travelers he gained a picture of this world which he could not reconcile with his own.

His first impression of a large continent broken by widely separated holdings of a frontier type remained. In addition there was knowledge of a feudal government, petty lordlings holding title to lands over men of lesser birth.

Kaluf and his men had a mild contempt for their customers. Their own homeland lay to the southeast, where, in some coastal cities, they had built up an overseas trade, retaining its cream for their own consumption, peddling the rest in the barbarous hinterland. Craike, his facility in their click speech growing, asked questions which the Master answered freely enough.

"These inland men know no difference between Saludian silk and the weaving of the looms in our own Kormonian quarter." He shrugged in scorn at such ignorance. "Why should we offer Salud when we can get Salud prices for Kormon lengths and the buyer is satisfied? Maybe—if these lords ever finish their private quarrels and live at peace so that there is more travel and they themselves come to visit in Larud or the other cities of the Children of Noe, then shall we not make a profit on lesser goods."

"Do these Lords never try to raid your caravans?"

Kaluf laughed. "They tried that once or twice. Certainly they saw there was the profit in seizing a train and paying nothing. But we purchased trail rights from the Black Hoods, and there was no more trouble. How is it with you, Ka-rak? Have you lords in your land who dare to stand against the power of the Hooded Ones?"

Craike, taking a chance, nodded. And knew he had been right when some reserve in Kaluf vanished.

"That explains much, perhaps even why such a man of power as you should be adrift in the wilderness. But you need not fear in this country, your brothers hold complete rule—"

A colony of Espers! Craike tensed. Had he, through some weird chance, found here the long-hoped-for refuge of his kind. But where was here? His old bewilderment was lost in a shout from the fore of the train.

"The outpost has sighted us and raised the trade banner." Kaluf quickened pace. "Within the hour we'll be at the walls of Sampur. Illif!"

Craike made for the head of the line. Sampur, by the reckoning of the train, was a city of respectable size, the domain of a Lord Ludicar with whom Kaluf had had mutually satisfactory dealings for some time. And the Master anticipated a profitable stay. But the man who had ridden out to greet them was full of news.

Racially he was unlike the traders, taller, longer of arm. His bare chest was a thatch of blond-red hair as thick as a bear's pelt, long braids swung across his shoulders. A leather cap, reinforced with sewn rings of metal, was crammed down over his wealth of hair, and he carried a shield slung from his saddle pad. In addition to sword and knife, he nursed a spear in the crook of his arm, from the point of which trailed a banner strip of blue stuff.

"You come in good time, Master. The Hooded Ones have proclaimed a horning, and all the outbounders have gathered as witnesses. This is a good day for your trading, the Cloudy Ones have indeed favored you. But hurry, the Lord Ludicar is now riding in and soon there will be no good place from which to watch—"

Craike fell back. Punishment? An execution? No, not quite that. He wished he dared ask questions. Certainly the picture which had leaped into Kaluf's mind at the mention of "horning" could not be true!

Caution kept the Esper aloof. Sooner or later his alien origin must be noted, though Kaluf had supplied him with a fur cap, leather jerkin, and boots from the caravan surplus.

The ceremony was to take place just outside the main gate of the stockade, which formed the outer rampart of the town. A group of braided, ring-helmed warriors hemmed in a more imposing figure with a feather plume and a blue cloak, doubtless Lord Ludicar. Thronging at a respectful distance were the townfolk. But they were merely audience; the actors stood apart.

Craike's hands went to his head. The emotion which beat at him from that party brought the metallic taste of fear to his mouth, aroused his own memories. Then he steadied, probed. There was terror there, broadcast from two figures under guard. Just as an impact of Esper power came from the three black-hooded men who walked behind the captives.

He used his own talent carefully, dreading to attract the attention of the men in black. The townsfolk opened an aisle in their ranks, giving free passage to the open moorland and the green stretch of forest not too far away.

Fear—in one of those bound, stumbling prisoners it was abject, the same panic which had hounded Craike into the desert. But, though the other captive had no hope, there was a thick core of defiance, a desperate desire to strike back. And something in Craike arose to answer that.

Other men, wearing black jerkins and no hoods, crowded about the prisoners. When they stepped back Craike saw that the drab clothing of the two had been torn away. Shame, blotting out fear, came from the smaller captive. And there was no mistaking the sex of the curves that white body displayed. A girl, and very young. A violent shake of her head loosened her hair to flow, black and long, clothing her nakedness. Craike drew a deep breath as he had before that plunge into the canyon. Moving quickly he crouched behind a bush.

The Black Hoods went about their business with dispatch, each drawing in turn certain designs and lines in the dust of the road until they had created an intricate pattern about the feet of the prisoners.

A chant began in which the townspeople joined. The fear of the male captive was an almost visible cloud. But the outrage and anger of his feminine companion grew in relation to the chant, and Craike could sense her will battling against that of the assembly.

The watching Esper gasped. He could not be seeing what his eyes reported to his brain! The man was down on all fours, his legs and arms stretched, a mist clung to them, changed to red-brown hide. His head lengthened oddly, horns sprouted. No man, but an antlered stag stood there.

And the girl—?

Her transformation came more slowly. It began and then faded. The power of the Black Hoods held her, fastening on her the form they visualized. She fought. But in the end a white doe sprang down the path to the forest, the stag leaping before her. They whipped past the bush where Craike had gone to earth, and he was able to see through the illusion. Not a red stag and a white doe, but a man and woman running for their lives, yet already knowing in their hearts there was no hope in their flight.

Craike, hardly knowing why he did it or who he could aid, followed, sure that mind touch would provide him with a guide.

He had reached the murky shadow of the trees when a sound rang from the town. At its summoning he missed a step before he realized it was directed against those he trailed and not himself. A hunting horn! So this world also had its hunted and its hunters. More than ever he determined to aid those who fled.

But it was not enough to just run blindly on the track of stag and doe. He lacked weapons. And his wits had not sufficed to save him in his own world. But there he had been conditioned against turning on his hunters, hampered, cruelly designed from birth to accept the quarry role. That was not true here.

Esper power—Craike licked dry lips. Illusions so well done they had almost enthralled him. Could illusion undo what illusion had done? Again the call of the horn, ominous in its clear tone, rang in his ears, set his pulses to pounding. The fear of those who fled was a cord, drawing him on.

But as he trotted among the trees Craike concentrated on his own illusion. It was not a white doe he pursued but the slim, young figure he had seen when they stripped away the clumsy stuff which had cloaked her, before she had shaken loose her hair veil. No doe, but a woman. She was not racing on four hooved feet, but running free on two, her hair blowing behind her. No doe, but a maid!

And in that moment, as he constructed that picture clearly, he contacted her in thought. It was like being dashed by sea-spray, cool, remote, very clean. And, as spray, the contact vanished in an instant, only to return.

"Who are you?"

"One who follows," he answered, holding to his picture of the running girl.

"Follow no more, you have done what was needful!" There was a burst of joy, so overwhelming a release from terror that it halted him. Then the cord between them broke.

Frantically Craike cast about seeking contact. There was only a dead wall. Lost, he put out a hand to the rough bark of the nearest tree. Wood things lurked here, them only did his mind touch. What did he do now?

His decision was made for him. He picked up a wave of panic again—spreading terror. But this was the fear of feathered and furred things. It came to him as ripples might run on a pool.

Fire! He caught the thought distorted by bird and beast mind. Fire which leaped from tree crown to tree crown, cutting a gash across the forest. Craike started on, taking the way west, away from the menace.

Once he called out as a deer flashed by him, only to know in the same moment that this was no illusion but an animal. Small creatures tunnelled through the grass. A dog fox trotted, spared him a measuring gaze from slit eyes. Birds whirred, and behind them was the scent of smoke.

A mountain of flesh, muscle and fur snarled, reared to face him. But Craike had nothing to fear from any animal. He confronted the great red bear until it whined, shuffled its feet and plodded on. More and more creatures crossed his path or ran beside him for a space.

It was their instinct which brought them, and Craike, to a river. Wolves, red deer, bears, great cats, foxes and all the rest came down to the saving water. A cat spat at the flood, but leaped in to swim. Craike lingered on the bank.

The smoke was thicker, more animals broke from the wood to take to the water. But the doe—where was she?

He probed, only to meet that blank. Then a spurt of flame ran up a dead sapling, advance scout of the furnace. He yelped as a floating cinder stung his skin and took to the water. But he did not cross, rather did he swim upstream, hoping to pass the flank of the fire and pick up the missing trail again.

Chapter 3

Smoke cleared as Craike trod water. He was beyond the path of the fire, but not out of danger. For the current against which he had fought his way beat here through an archway of masonry. Flanking that arch were two squat towers. As an erection it was far more ambitious than anything he had seen during his brief glimpse of Sampur. Yet, as he eyed it more closely, he could see it was a ruin. There were gaps in the narrow span across the river, a green bush sprouted from the summit of the far tower.

Craike came ashore, winning his way up the steep bank by handholds of vine and bush no alert castellan would have allowed to grow. As he reached a terrace of cobbles stippled with bunches of coarse grass, a sweetish scent of decay drew him around the base of the tower to look down at a broad ledge extending into the river. Piled on it were small baskets and bowls, some so rotted that only outlines were visible. Others new and all filled with mouldering food stuffs. But those who left such offerings must have known that the tower was deserted.

Puzzled Craike went back to the building. The stone was undressed, yet the huge blocks which formed its base were fitted together with such precision that he suspected he could not force the thin blade of a pocket knife into any crack. There had been no effort at ornamentation, at any lighting of the impression of sullen, brute force.

Wood, split and insect bored, formed a door. As he put his hand to it Craike discovered the guardian the long-ago owners of the fortress had left in possession. His hands went to his head, the blow he felt might have been physical. Out of the stronghold before him came such a wave of utter terror and dark promise as to force him back. But no farther than the edge of the paved square about the building's foundation.

Grimly he faced that challenge, knowing it for stored emotion and not the weapon of an active will. He had his own defense against such a formless enemy. Breaking a dead branch from a bush, he twisted about it whisps of the sun-bleached grass until he had a torch of sorts. A piece of smoldering tinder blown from the fire gave him a light.

Craike put his shoulder to the powdery remnants of the door, bursting it wide. Light against dark. What lurked there was nourished by dark, fed upon the night fears of his species.

A round room, bare except for some crumbling sticks of wood, a series of steps jutting out from the wall to curl about and vanish above. Craike made no move toward further exploration, holding up the torch, seeking to see the real, not the threat of this place.

Those who had built it possessed Esper talents. And they had used that power for twisted purposes. He read terror and despair trapped here by the castellans' art, horror, an abiding fog of what his race considered evil.

Tentatively Craike began to fight. With the torch he brought light and heat into the dark and cold. Now he struggled to offer peace. Just as he had pictured a girl in flight in place of the doe, so did he now force upon those invisible clouds of stored suffering calm and hope. The gray window slits in the stone were uncurtained to the streaming sunlight.

Those who had set that guardian had not intended it to hold against an Esper. Once he began the task, Craike found the opposition melting. The terror seeped as if it sank into the floor wave by wave. He stood in a room which smelt of damp and, more faintly, of the rotting food piled below its window slits; but now it was only an empty shell.

Craike was tired, drained by his effort. And he was puzzled. Why had he fought for this? Of what importance to him was the cleansing of a ruined tower?

Though to stay here had certain advantages. It had been erected to control river traffic. Though that did not matter for the present, just now he needed food more—

He went back to the rock of offerings, treading a wary path through the disintegrating stuff. Close to the edge he came upon a clay bowl containing coarsely ground grain and, beside it, a basket of wilted leaves filled with overripe berries. He ate in gulps.

Grass made him a matted bed in the tower, and he kindled a fire. As he squatted before its flames, he sent out a questing thought. A big cat drank from the river. Craike shuddered away from that contract with blood lust. A night-hunting bird provided a trace of awareness. There were small rovers and hunters. But nothing human.

Tired as he was Craike could not sleep. There was the restless sensation of some demand about to be made, some task waiting. From time to time he fed the fire. Towards morning he dozed, to snap awake. A night creature drinking, a screech overhead. He heard the flutter of wings echo hollowly through the tower.

Beyond—darkness—blank, that curious blank which had fallen between him and the girl. Craike got to his feet eagerly. That blank could be traced.

Outside it was raining, and fog hung in murky bands among the river hollows. The blank spot veered. Craike started after it. The tower pavement became a trace of old road he followed, weaving through the fog.

There was the sour smell of old smoke. Charred wood, black muck clung to his feet. But his guide point was now stationary as the ground rose, studded with outcrops of rock. So Craike came to a mesa jutting up into a steel-gray sky.

He hitched his way up by way of a long-ago slide. The rain had stopped, but there was no hint of sun. And he was unprepared for the greeting he met as he topped the lip of a small plateau.

A violent blow on the shoulder whirled him halfway around, and only by a finger's width did he escape a fall. A cry echoed his, and the blank broke. She was there.

Moving slowly, using the same technique he knew to soothe frightened animals, Craike raised himself again. The pain in his shoulder was sharp when he tried to put much weight upon his left arm. But now he saw her clearly.

She sat cross-legged, a boulder at her back, her hair a rippling cloud of black through which her hands and arms shown starkly white. She had the thin, three-cornered face of a child who has known much harshness; there was no beauty there—the flesh had been too much worn by spirit. Only her eyes, watchful-wary as those of a feline, considered him bleakly. In spite of his beam of good will, she gave him no welcome. And she tossed another stone from hand to hand with the ease of one who had already scored with such a weapon.

"Who are you?" she spoke aloud.

"He who followed you," Craike fingered the bruise wound on his shoulder, not taking his eyes from hers.

"You are no Black Hood." It was a statement not a question. "But you, also, have been horned." Another statement.

Craike nodded. In his own time and place he had indeed been "horned."

Just as her thrown stone had struck without warning, so came her second attack. There was a hiss. Within striking distance a snake flickered a forked tongue.

Craike did not give ground. The snake head expanded, fur ran over it; there were legs, a plume of tail fluffed. A dog fox yapped once at the girl and vanished. Craike read her recoil, the first faint uncertainty.

"You have the power!"

"I have power," he corrected her.

But her attention was no longer his. She was listening to something he could hear with neither ear nor mind. Then she ran to the edge of the mesa. He followed.

On this side the country was more rolling, and across it now came mounted men moving in and out of mist pools. They rode in silence, and over them was the same blanketing of thought as the girl had used.

Craike glanced about. There were loose stones, and the girl had already proven her marksmanship with such. But they would be no answer to the weapons the others had. Only flight was no solution either.

The girl sobbed once, a broken cry so unlike the iron will she had shown that Craike started. She leaned perilously over the drop, staring down at the horsemen.

Then her hands moved with desperate speed. She tore hairs from her head, twisted and snarled them between her fingers, breathed on them, looped them with a stone for weight, casting the tangled mass out to land before the riders.

The mist curled, took on substance. Where there had been only rock there was now a thicket of thorn, so knotted that no fleshed creature could push through it. The hunters paused, then they rode on again, but now they drove a reeling, naked man, a man kept going by a lashing whip whenever he faltered.

Again the girl sobbed, burying her face in her hands. The wretched captive reached the thorn barrier. Under his touch it melted. He stood there, weaving drunkenly.

A whip sang. He went to his knees under its cut, a trapped animal's wail on the wind. Slowly, with a blind seeking, his hands went out to small stones about him. He gathered them, spread them anew in patterns. The girl had raised her head, watched dry-eyed, but seething with hate and the need to strike back. But she did not move.

Craike dared lay a hand on her narrow shoulder, feeling through her hair the chill of her skin, while the hair itself clung to his fingers as if it had the will to smother and imprison. He tried to pull her away, but he could not move her.

The naked man crouched in the midst of his pattern, and now he chanted, a compelling call the girl could not withstand. She wrenched free of Craike's hold. But as she went she spared a thought for the man who had tried to save her. She struck out, her fist landing on the stone bruise. Pain sent him reeling back as she went over the rim of the mesa, her face a mask which no friend nor enemy might read. But there was no resignation in her eyes as she was forced to the meeting below.

Chapter 4

By the time Craike reached a vantage point the girl stood in the center of the stone ring. Outside crouched the man, his head on his knees. She looked down at him, no emotion showing on her wan face. Then she dropped her hand on his thatch of wild hair. He jerked under that touch as he had under the whip which had printed the scarlet weals across his back and loins. But he raised his head, and from his throat came a beast's mournful howl. At her gesture he was quiet, edging closer to her as if seeking some easement of his suffering.

The Black Hood drew in. Craike's probe could make nothing of them. But they could not hide their emotions as well as they concealed their thoughts. And the Esper recoiled from the avid blood lust which lapped at the two by the cliff.

A semicircle of the black-jerkined retainers moved too. And the man who had led them lay on the earth now, moaning softly. But the girl faced them, head unbowed. Craike wanted to aid her. Had he time to climb down the cliff? Clenching his teeth against the pain movement brought to his shoulder, the Esper went back, holding a mind shield as a frail protection.

Directly before him now was one of the guards. His mount caught Craike's scent, stirred uneasily, until the quieting thought of the Esper held it steady. Craike had never been forced into such action as he had these past few days; he had no real plan now, it must depend upon chance and fortune.

As if the force of her enemies' wills had slammed her back against the rock, the girl was braced by the cliff wall, a black and white figure.

Mist swirled, took on half substance of a monstrous form, was swept away in an instant. A clump of dried grass broke into flame, sending the ponies stamping and snorting. It was gone, leaving a black smudge on the earth. Illusions, realities—Craike watched. This was so far beyond his own experience that he could hardly comprehend the lightning moves of mind against mind. But he sensed these others could beat down the girl's resistance at any moment they desired, that her last futile struggles were being relished by those who decreed this as part of her punishment.

And Craike, who had believed that he could never hate more than he had when he had been touched by the fawning "hound" of the mob, was filled with a rage tempered into a chill of steel determination.

The girl went to her knees, still clutching her hair about her, facing her tormenters with her still-held defiance. Now the man who had wrought the magic which had drawn her there crawled, all humanity gone out of him, wriggling on his belly back to his captors.

Two of the guards jerked him up. He hung limp in their hands, his mouth open in an idiot's grin. Callously, as he might tread upon a worm, the nearest Black Hood waved a hand. A metal axe flashed, and there came the dull sound of cracking bone. The guards pitched the body from them so that the bloodied head almost touched the girl.

She writhed, a last frenzied attempt to break the force which pinned her. Without haste the guards advanced. One caught at her hair, pulling it tautly from her head.

Craike shivered. The thrill of her agony reached him. This was what she feared most, fought so long to prevent. If ever he must move now. And that part of his brain which had been feverishly seeking a plan went into action.

Ponies pawed, reared, went wild with panic. One of the Black Hoods swung around to face the terrorized animals. But his own mount struck out with teeth and hooves. Guardsmen shouted, and above their cries arose the shrill squeals of the animals.

Craike stood his ground, keeping the ponies in terror-stricken revolt. The guard who held the handful of hair slashed at the tress with his knife, severing it at a palm's distance away from her head. But in that same moment she moved. The knife leaped free from the man's grasp, while the severed hair twined itself about his hands, binding them until the blade buried itself in his throat; and he went down.

One of the Black Hoods was also finished, tramped into a feebly squirming thing by the ponies. Then from the ground burst a sheet of flame which split into balls, drifting through the air or rolling along the earth.

The Esper wet his lips—that was not his doing! He did not have to feed the panic of the animals now; they were truly mad. The girl was on her feet. Before his thought could reach her she was gone, swallowed up in a mist which arose to blanket the fire balls. Once more she cut their contact; there was a blank void where she had been.

Now the fog thickened. Through it came one of the ponies, foam dripping from its blunt muzzle. It bore down on Craike, eyes gleaming red through a tangled forelock. With a scream it reared.

Craike's hand grabbed a handful of mane as he leaped, avoiding teeth and hooves. Then, somehow, he gained the pad saddle, locking his fingers in the coarse hair, striving to hold his seat against the bucking enraged beast. It broke into a run, and the Esper plastered himself to the heaving body. For the moment he made no attempt at mind control.

Behind, the Black Hoods came out of their stunned bewilderment. They were questing feverishly, and he had to concentrate on holding his shield against them. A pony fleeing in terror would not excite them; a pony under control would provide them with a target.

Later he could circle about and try to pick up the trail of the witch girl. Flushed with success, Craike was sure he could provide her with a rear guard no Black Hood could pass.

The fog was thick, and the pace of the pony began to slacken. Once or twice it bucked half-heartedly, giving up when it could not dislodge its rider. Craike drew his fingers in slow, soothing sweeps down the sweating curve of its neck.

There were no more trees about, and the unshod hooves pounded on sand. They were in a dried water course, and Craike did not try to turn from that path. Then his luck ran out.

What he had ignorantly supposed to be a rock ahead, heaved up seven feet or more. A red mouth opened in a great roar. He had believed the bear he had seen fleeing the fire to be a giant, but this one was a nightmare monster.

The pony screamed with an almost human note of despair and whirled. Craike gripped the mane again and tried to mind control the bear. But his surprise had lasted seconds too long, A vast clawed paw struck, ripping across pony hide and human thigh. Then Craike could only cling to the running mount.

How long he was able to keep his seat he never knew.

Then he slipped; there was a throb of pain as he struck the ground, to be followed by blackness.

It was dusk when he opened his eyes, fighting agony in his head, his leg. But later there was moonlight. And that silver-white spotlighted a waiting shape. Green slits of eyes regarded him remotely. Dizzily he made contact.

A wolf—hungry—yet with a wariness which recognized in the prone man an enemy. Craike fought for control. The wolf whined, then it arose, its prick ears sharp cut in the moonlight, its nose questing for the scent of other, less disturbing prey, and it was gone.

Craike edged up against a boulder and sorted out sounds. The rush of water. He moved a paper-dry tongue over cracked lips. Water to drink—to wash his wounds— water!

With a groan Craike worked his way to his feet, holding fast to the top of the rock when his torn leg threatened to buckle under him. The same inner drive which had kept him going through the desert brought him down to the river.

By sunrise he was seeking a shelter, wanting to lie up, as might the wolf, in some secret cave until his wounds healed. All chance of finding the witch girl was lost. But as he crawled along the shingle, leaning on a staff he had found in drift wood, he kept alert for any trace of the Black Hoods.

It was mid morning on the second day that his snail's progress brought him to the river towers. And it took another hour for him to reach the terrace. Gaunt and worn, his empty stomach complaining, he wanted nothing more than to sink down in the nest of grass be had gathered and cease to struggle.

Perhaps he might have done so had not a click-clack of sound from the river put him on the defensive, his staff now a club. But these were not Black Hoods. Farmers, local men bound for the market of Sampur with products of their fields. They had paused, were making a choice among the least appetizing of their wares for a tribute to be offered to the tower demon.

Craike hitched stiffly to a point where he could witness that sacrifice. But when he assessed the contents of their dugout, the heaping basket piled between the paddlers, his hunger took command.

Fob off a demon with a handful of meal and a too-ripe melon, would they? With three haunches of cured meat and all that other stuff on board!

Craike voiced a roar which could have done credit to the red bear, a roar which altered into a demand for meat. The paddlers nearly lost control of their crude craft. But one reached for a haunch and threw it blindly on the refuse-covered rock, while his companion added a basket of small cakes into the bargain.

"Enough, little men—" Craike's voice boomed hollowly. "You may pass free."

They needed no urging, they did not look at those threatening towers as their paddles bit into the water, adding impetus to the pull of the current.

Craike watched them well out of sight before he made a slow descent to the rock. The effort he was forced to expend warned him that a second such trip might be impossible, and he inched back to the terrace dragging both meat and cakes.

The cured haunch he worried into strips, using his pocket knife. It was tough, not too pleasant to the taste and unsalted. But he found it more appetizing than the cakes of baked meal. With this supply he could afford to lie up and favor his leg.

About the claw rents the flesh was red and puffed. Craike had no dressing but river water and the leaves he had tied over the tears. Sampur was beyond his power to reach, and to contact men traveling on the river would only bring the Black Hoods.

He lay in his grass nest and tried to sort out the events of the past few days. This was a land in which Esper powers were allowed free range. He had no idea of how he had come here, but it seemed to his feverish mind that he had been granted another chance—one in which the scales of justice were more balanced in his favor. If he could only find the girl, learn from her—

Tentatively, without real hope, he sent out a questing thought. Nothing. He moved impatiently, wrenching his leg, so that his head swam with pain. Throat and mouth were dry. The lap of water sounded in his ears. Water—he was thirsty again. But he could not crawl down slope and up once more. Craike closed his eyes wearily.

Chapter 5

Craike’s memory of the hours which followed thereafter was dim. HAD he seen a demon in the doorway? A slavering wolf? A red bear?

Then the girl sat there, cross-legged as he had seen her on the mesa, her cloak of hair about her. A hand emerged from the cloak to lay wood on the fire. Illusions?

But would an illusion turn to him, put firm, cool fingers upon his wound, somehow driving out by touch the pain and fire which burned there? Would an illusion raise his head, cradling it against her so that the soft silk of her hair lay against his cheek and throat, urging on him liquid out of a crude bowl? Would an illusion sing softly to herself while she drew a fish-bone comb back and forth through her hair, until the song and the sweep of the comb lulled him into a sleep so deep that no dream walked there?

He awoke, clear headed. Yet that last illusion lingered. For she came from the sun-drenched world without, a bowl of fruit in her hand. For a long moment she stood gazing at him searchingly. But when he tried mind contact, he met that wall. Not unheeding—but a refusal to answer.

Her hair was now braided. But about her face the lock which the guardsman had shorn made an untidy fringe. While around her thin body was a strip of hide, purposefully arranged to mask all femininity.

"So," Craike spoke rustily, "you are real—"

She did not smile. "I am real. You no longer dream with fever."

"Who are you?" He asked the first of his long-hoarded questions.

"I am Takya." She added nothing to that.

"You are Takya, and you are a witch—"

"I am Takya, and I have the power." It was an assertion of fact rather than agreement.

She settled in her favorite cross-legged position, selected a fruit from her bowl and examined it with the interest of a housewife who has shopped for supplies on a limited budget. Then she placed it in his hand before she chose another for herself. He bit into the plumlike globe. If she would only drop her barrier, let him communicate in the way which was fuller and deeper than speech.

"You also have the power—"

Craike decided to be no more communicative than she. He replied to that with a curt nod.

"Yet you have not been horned—"

"Not as you have been. But in my own world, yes."

"Your world?" Her eyes held some of the feral glow of a hunting cat's. "What world, and why were you horned there, man of sand and ash, power?"

Without knowing why Craike related the events of the days past. Takya listened, he was certain, with more than ears alone. She picked up a stick from the pile of firewood and drew patterns in the sand and ash, patterns which had something to do with her listening.

"Your power was great enough to break a world wall." She snapped the stick between two fingers, threw it into the flames.

"A world wall?"

"We of the power have long known that different worlds lie together in such a fashion." She held up her hand i with the fingers tight lying one to another. "Sometimesj there comes a moment when two touch so closely that thel power can carry one through. If at that moment there is a: desperate need for escape. But those places of meeting can not be readily found, and the moment of their touch can lay only for an instant. Have you in your world no reports of men and women who have vanished almost in sight of their fellows?"

Remembering old tales he nodded.

"I have seen a summoning from another world," she continued with a shiver, running both hands down the length of her braids as if so she evoked a shield for both mind and body. "To summon so is a great evil, for no man can hold in check the power of something alien. You broke the will of the Black Hoods when I was a beast running from their hunt. When I made the serpent to warn you off, you changed it into a fox. And when the Black Hoods would have shorn my power—" she looped the braids about her wrists, caressing, treasuring them against her small breasts, "again you broke their hold and set me free for a second time. But this you could not have done had you been born into this world, for our power must follow set laws. Yours lies outside out patterns and can cut across those laws—even as the knife cut this—" She touched the rough patch of hair at her temple.

"Follow patterns? Then it was those patterns in stone which drew you down from the mesa?"

"Yes. Takyi, my womb-brother, whom they slew there, was blood of my blood, bone of my bone. When they crushed him, then they could use him to draw me, and I could not resist. But in the slaying of his husk they freed me—to their great torment, as Tousuth shall discover in time."

"Tell me of this country. Who are the Black Hoods and why did they horn you? Are you not of their breed since you have the power?"

But Takya did not answer at once in words. Nor did she, as he had hoped, lower her mind barrier.

Her fingers now held one long hair she had pulled from her head, and this she began to weave in and out, swiftly intricately, in a complicated series of loops and crossed strands. After a moment Craike did not see the white fingers, nor the black hair they passed in loops from one to another. Rather did he see the pictures she wrought in her weaving.

A wide land, largely wilderness. The impressions he had gathered from Kaluf and the traders crystalized into vivid life. Small holdings here and there, ruled by petty lords, new settlements carved out by a scattered people moving up from the south in great wheeled wains, bringing flocks and herds, their carefully treasured seed. Stopping here and there for a season to sow and reap, until they decided upon a site for their final rooting. Tiny city-states, protected by the Black Hoods—the Esper born who purposefully interbred their own gifted stock, keeping their children apart.

Takya and her brother coming, as was sometimes—if rarely—true, from the common people. Carefully watched by the Black Hoods. Then discovered to be a new mutation, condemned as such to be used for experimentation. But for a while protected by the local lord who wanted Takya.

But he might not take her unwilling. For the power that was hers as a virgin was wholly rift from her should she be forced. And he had wanted that power, obedient to him, as a check upon the monopoly of the Black Hoods. So with some patience he had set himself to a peaceful wooing. But the Black Hoods had moved first.

Had they accomplished her taking, the end they had intended for her was not as easy as death. And she wove a picture of it, with all its degradation and shame stark and open, for Craike's seeing.

"Then the Hooded ones are evil?"

"Not wholly." She untwisted the hair and put it with care into the fire. "They do much good, and without them people would suffer. But I, Takya, am different. And after me, when I mate, there will be others also different. How different we are not yet sure. The Hooded Ones want no change, by their thinking that means disaster. So they would use me to their own purposes. Only I, Takya, shall not be so used!"

"No, you shall not." The vehemence of his own outburst startled him. Craike wanted nothing so much at that moment than to come to grips with the Black Hoods, who had planned this systematic hunt.

"What will you do now?" He asked more calmly, wishing she would share her thoughts with him.

"This is a strong place. Did you cleanse it?"

He nodded impatiently.

"So I thought. That was also a task one born to this world might not have performed. But those who pass are not yet aware of the Cleansing. They will not trouble us, but pay tribute."

Craike found her complacency irritating. To lie up here and live on the offerings of river travelers did not appeal to him.

"This stone piling is older work than Sampur and much better," she continued. "It must have been a fortress for some of those forgotten ones who held lands and then vanished long before we came from the south. If it is repaired no lord of this district would have so good a roof."

"Two of us to rebuild it?" he laughed.

"Two of us—working thus."

A block of stone, the size of a brick, which had fallen from the sill of one of the needle-narrow windows, arose slowly in the air, settled into the space from which it had tumbled. Illusion or reality? Craike got to his feet and lurched to the window. His hand fell upon the stone which moved easily in his grasp. He took it out, weighed it, and then gently returned it to its place. Not illusion.

"But illusion too—if need be." There was, for the first time, a warm note of amusement in her tone. "Look on your tower, river lord!"

He limped to the door. Outside it was warm, sunny, but it was a site of ruins. Then the picture changed. Brown drifts of grass vanished from the terrace, the fallen stone was all in place. A hard-faced sentry stood wary-eyed on a repaired river arch. Another guardsman led out ponies saddle-padded and ready, other men were about garrison tasks.

Craike grinned. The sentry on the arch lost his helm, his jerkin. He now wore the tight tunic of the Security Police, his spear was a gas rifle. The ponies misted, and in their place a speedster sat on the stone. He heard her laugh.

"Your guard, your traveling machine. But how grim, ugly. This is better!"

Guards, machine, all were swept away. Craike caught his breath at the sight of delicate winged creatures dancing in the air, displaying a joy of life he had never known. Fawns, little people of the wild, came to mingle with such shapes of beauty and desire that at last he turned his head away.

"Illusion," her voice was hard, mocking.

But Craike could not believe that what he had seen had been born from hardness and mockery.

"All illusions. We shall be better now with warriors. As for plans, can you suggest any better than to remain here and take what fortune sends—for a space?"

"Those winged dancers—where?"

"Illusions!" She returned harshly. "But such games tire one. I do not think we shall conjure up any garrison before they are needed. Come, do not tear open those wounds of yours anew, for healing is no illusion and drains one even more of the power."

The clawed furrows were healing cleanly, though he would bear their scars for life. He hobbled back to the grass bed and dropped upon it, but regretted the erasure of the sprites she had shown him.

Once he was safely in place, Takya left with the curt explanation she had things to do. But Craike was restless, too much so to remain long inside the tower. He waited until she had gone and then, with the aid of his staff, climbed to the end of the span above the river. From here the twin tower on the other bank looked the same as the one from which he had come. Whether it was also haunted Craike did not know. But, as he looked about, he could see the sense of Takya's suggestion. A few illusion sentries would discourage any ordinary intrusion.

Takya's housekeeping had changed the rock of offerings. All the rotting debris was gone and none of the odor of decay now offended the nostrils at a change of wind. But at best it was a most uncertain source of supply. There could not be too many farms upriver, nor too many travelers taking the water way.

As if to refute that, his Esper sense brought him sudden warning of strangers beyond the upper bend. But, Craike tensed, there were no peasants bound for the market at Sampur. Fear, pain, anger, such emotions heralded their coming. There were three, and one was hurt. But they were not Esper, nor did they serve the Black Hoods. Though they were, or had been, fighting men.

A brutal journey over the mountains where they had lost comrades, the finding of this river, the theft of the dugout they now used so expertly—it was all there for him to read. And beneath that something else, which, when he found it, gave Craike a quick decision in their favor—a deep hatred of the Black Hoods! Outlaws, very close to despair, keeping on a hopeless trail because it was not in them to surrender.

Craike contacted them subtly. They must not think they were heading into an Esper trap! Plant a little hope, a faint suggestion that there was a safe camping place ahead, that was all he could do at present. But so he drew them on.

"No!" A ruthless order cut across his line of contact, striking at the delicate thread with which he was playing the strangers in. But Craike stood firm. "Yes, yes, and yes!"

He was on guard instantly. Takya, mistress of illusion as she had proved herself to be, might act. But surprisingly she did not. The dugout came into view, carried more by the current than the efforts of its crew. One lay full length in the bottom, while the bow paddler had slumped forward. But the man in the stern was bringing them in. And Craike strengthened his invisible, unheard invitation to urge him on.

Chapter 6

But Takya had not yet begun to fight. As the dugout swung in toward the offering ledge one of the Black Hoods' guardsmen appeared there, his drawn sword taking fire from the sun. The fugitive steersman faltered until the current drew his craft on. Craike caught the full force of the stranger's despair, all the keener for the hope of moments before. The Esper irritation against Takya flared into anger.

He made the illusion reel back, hands clutching at his breast from which protruded the shaft of an arrow. Craike had seen no bows here, but it was a weapon to suit this world. And this should prove to Takya he meant what he had said.

The steersman was hidden as the dugout passed under the arch. There was a scrap of beach, the same to which Craike had swum on his first coming. He urged the man to that, beaming good will.

But the paddler was almost done, and neither of his companions could aid him. He drove the crude craft to the bank, and its bow grated on the rough gravel. Then he crawled over the bodies of the other two and fell rather than jumped ashore, turning to pull up the canoe as best he could.

Craike started down. But he might have known that Takya was not so easily defeated. Though they maintained an alliance of sorts she accepted no order from him.

A brand was teleported from the tower fire, striking spear-wise in the dry brush along the slope. Craike's mouth set. He tried no more arguments. They had already tested power against power, and he was willing to so battle again. But this was not the time. However the fire was no illusion, and he could not fight it, crippled as he was. Or could he?

It was not spreading too fast—though Takya might spur it by the forces at her command. Now—there was just the spot! Craike steadied himself against a mound of fallen masonry and swept out his staff, dislodging a boulder and a shower of gravel. He had guessed right. The stone rolled to crush out the brand, and the gravel he continued to push after it smothered the creeping flames.

Red tongues dashed spitefully high in a sheet of flame, and Craike laughed. THAT was illusion. She was angry. He produced a giant pail in the air, tilted it forward, splashed its contents into the heart of that conflagration. He felt the lash of her rage, standing under it unmoved. So might she bring her own breed to heel, but she would learn he was not of that ilk.

"Holla!" That call was no illusion, it begged help.

Craike picked a careful path downslope until he saw the dugout and the man who had landed it. The Esper waved an invitation and at his summons the fugitive covered the distance between them.

He was a big man of the same brawny race as those of Sampur, his braids of reddish hair hanging well below his wide shoulders. There was the raw line of a half-healed wound down the angle of his jaw, and his sunken eyes were very tired. For a moment he stood downslope from Craike, his hands on his hips, his head back, measuring the Esper with the shrewdness of a canny officer who had long known how to judge and handle raw levies.

"I am Jorik of the Eagles’ Tower." The statement was made with the same confidence as the announcement of rank might have come from one of the petty lords. "Though," he shrugged, "the Eagles’ Tower stands no more with one stone upon the other. You have a stout lair here—" he hesitated before he concluded, "friend.''

"I am Craike," the Esper answered as simply, "and I am also one who has run from enemies. This lair is an old one, though still useful."

"Might the enemies from whom you run wear black hoods?" countered Jorik. "It seems to me that things I have just seen here have the stink of that about them."

"You are right. I am no friend to the Black Hoods."

"But you have the power—"

"I have power," Craike tried to make the distinction clear. "You are welcome, Jorik. So all are welcome here who are no friends to Black Hoods."

The big warrior shrugged. "We can no longer run. If the time has come to make a last stand, this is as good a place as any. My men are done." He glanced back at the two in the dugout. "They are good men, but we were pressed when they caught us in the upper pass. Once there were twenty hands of us," he held up his fist and spread the fingers wide for counting. "They drew us out of the tower with their sorcerers' tricks, and then put us to the hunt."

"Why did they wish to make an end to you?"

Jorik laughed shortly. "They dislike those who will not fit into their neat patterns. We are free mountain men, and no Black Hood helped us win the Eagles’ Tower, none aided us to hunt. When we took our furs down to the valley they wanted to levy tribute. But what spell of theirs trapped the beasts in our dead-falls, or brought them to our spears? We pay not for what we have not bought. Neither would we have made war on them. Only, when we spoke out and said it so, there were others who were encouraged to do likewise, and the Black Hoods must put an end to us before their rule was broken. So they did."

"But they did not get all of you," Craike pointed out. "Can you bring your men up to the tower? I have been hurt and can not walk without support or I would lend you a hand."

"We will come." Jorik returned to the dugout. Water was splashed vigorously into the face of the man in the bow, arousing him to crawl ashore. Then the leader of the fugitives swung the third man out of the craft and over his shoulder in a practiced carry.

When Craike had seen the unconscious man established on his own grass bed, he stirred up the fire and set out food. While Jorik returned to the dugout to bring in their gear.

Neither of the other men were of the same size as their leader. The one who lay limp, his breath fluttering between his slack lips, was young hardly out of boyhood, his thin frame showing bones rather than muscled flesh under the rags of clothing. The other was short, dark-skinned, akin by race to Kaluf s men, his jaw sprouting a curly beard. He measured Craike with suspicious glances from beneath lowered red lids, turning that study to the walls about him and the unknown reaches at the head of the stair.

Craike did not try mind touch. These men were rightly suspicious of Esper arts. But he did attempt to reach Takya, only to meet that nothingness with which she cloaked her actions. Craike was disturbed. Surely now that she was convinced he was determined to give the harborage to the fugitives, she would oppose him. They had nothing to fear from Jorik and his men, but rather would gain by joining forces.

Until his wounds were entirely healed he could not go far. And without weapons they would have to rely solely upon Esper powers for defense. Having witnessed the efficiency of the Hooded Ones' attack, Craike doubted a victory in any engagement to which those masters came fully prepared. He had managed to upset their spells merely because they had not known of his existence. But the next time he would have no such advantage.

On the other hand the tower could be defended by force of arms. With bows— Craike savored the idea of archers giving a Hooded force a devastating surprise. The traders had had no such arm, as sophisticated as they were. And he had seen none among the warriors of Sampur. He'd have to ask Jorik if such were known.

In the meantime he sat among his guests, watching Jorik feed the semi-conscious boy with soft fruit pulp and the other man wolf down dried meat. When the latter had done, he hitched himself closer to the fire and jerked a thumb at his chest.

"Zackuth," he identified himself.

"From Larud?" Craike named the only city of Kaluf's people he could remember.

The dark man's momentary surprise had no element of suspicion. "What do you know of the Children of Noe, stranger?"

"I journeyed the plains with one called Kaluf, a Master Trader of Larud."

"A fat man who laughs much and wears a falcon plume in his cap?"

"Not so," Craike allowed a measure of chill to ice his reply. "The Kaluf who led this caravan was a lean man who knew the edge of a good blade from its hilt. As for cap ornaments—he had a red stone to the fore of his. Also he swore by the Eyes of the Lady Lor,"

Zackuth gave a great bray of laughter. "You are no stream fish to be easily hooked, are you, tower dweller? I am not of Larud, but I know Kaluf, and those who travel in his company do not wear one badge one day and another the next. But, by the looks of you, you have fared little better than we lately. Has Kaluf also fallen upon evil luck?"

"I traveled safely with his caravan to the gates of Sampur. How it fared with him thereafter I can not tell you."

Jorik grinned and settled his patient back on the bed. "I believe you must have parted company in haste, Lord Ka-rak?"

Craike answered that with the truth. "There were two who were horned. I followed them to give what aid I could."

Jorik scowled, and Zackuth spat into the fire.

"We were not horned; we have no power," the latter remarked. "But they have other tricks to play. So you came here?"

"I was clawed by a bear," Craike supplied a meager portion of his adventures, "and came here to lie up until I can heal me of that hurt."

"This is a snug hole," Jorik was appreciative. "But how got you such eating?" He popped half a fruit into his mouth and licked his juicy fingers. "This is no wilderness feeding."

"The tower is thought to be demon-haunted. Those taking passage down stream leave tribute."

Zackuth slapped his knee. "The Gods of the Waves are good to you, Lord Ka-rak, that you should stumble into such fortune. There is more than one kind of demon for the haunting towers. How say you, Lord Jorik?"

"That we have also come into luck at last, since Lord Ka-rak has made us free of this hold. But perhaps you have some other thought in your head?" He spoke to the Esper.

Craike shrugged. "What the clouds decree shall fall as rain or snow," he quoted a saying of the caravan men.

It was close to sunset, and he was worried about Takya. He could not believe that she had gone permanently. And yet, if she returned, what would happen? He had been careful not to use Esper powers. Takya would have no such compunctions.

He could not analyze his feelings about her. She disturbed him, awoke emotions he refused to face. There was a certain way she had of looking sidewise— But her calm assumption of superiority pricked beneath his surface armor. And the antagonism fretted against the feeling which had drawn him after her from the gates of Sampur. Once again he sent out a quest-thought and, to his surprise, was answered.

"They must go!"

"They are outlaws, even as we. One is ill, the others worn with long running. But they stood against the Black Hoods. As such they have a claim on roof, fire and food from us."

"They are not as we!" Again arrogance. "Send them or I shall drive them. I have the power—"

"Perhaps you have the power, but so do I!" He put all the assurance he could muster into that. "I tell you, no better thing could happen then for us to give these men aid. They are proven fighters—"

"Swords can not stand against the power!"

Craike smiled. His plans were beginning to move even as he carried on this voiceless argument. "Not swords, no, Takya. But all fighting is not done with swords or spears. Nor with the power either. Can a Black Hood think death to his enemy when he himself is dead, killed from a distance, and not by mind power his fellows could trace and be armored against.

He had caught her attention. She was acute enough to know that he was not playing with words, that he knew of what he spoke. Quickly he built upon that spark of interest. "Remember how your illusion guard died upon the offering rock when you would warn off these men?"

"By a small spear." She was contemptuous again.

"Not so." He shaped a picture of an arrow and then of an archer releasing it from the bow cord, of its speeding true across the river to strike deep into the throat of an unsuspecting Black Hood.

"You have the secret of this weapon?"

"I do- And five such arms are better than two, is that not the truth?"

She yielded a fraction. "I will return. But they will not like that."

"If you return, they will welcome you. These are no hunters of witch maidens—" he began, only to be disconcerted by her obvious amusement. Somehow he had lost his short advantage over her. Yet she did not break contact.

"Ka-rak, you are very foolish. No, these will not try to mate with me, not even if I willed it so. As you will see. Does the eagle mate with the hunting cat? But they will be slow to trust me, I think. However, your plan has possibilities, and we shall see."

Chapter 7

Takya had been right about her reception by the fugitives. They knew her for what she was, and only Craike's acceptance of her kept them in the tower. That and the fact, which Jorik did not try to disguise, that they could not hope to go much farther on their own. But their fears were partly allayed when she took over the nursing of the sick youngster, using on him the same healing power she had produced for Craike's wound. By the new day she was feeding him broth and demanding service from the others as if they had been her liegemen from birth.

The sun was well up when Jorik came in whistling from a dip in the river.

"This is a stout stronghold, Lord Ka-rak. And with the power aiding us to hold it, we are not likely to be shaken out in a hurry. Doubly is that true if the Lady aids us."

Takya laughed. She sat in the shaft of light from one of the narrow windows, combing her hair. Now she looked over her shoulder at them with something approaching a pert archness. In that moment she was more akin to the women Craike had known in his own world.

"Let us first see how the Lord Ka-rak proposes to defend us." There was mockery in that, enough to sting, as well as a demand that he make good his promise of the night before.

But Craike was prepared. He discarded his staff for a hold on Jorik's shoulder, while Zackuth slogged behind. They climbed into the forest. Craike had never fashioned a bow, and he did not doubt that his first attempts might be failures. But, as the three made their slow progress, he explained what they must look for and the kind of weapon he wanted to produce. They returned within the hour with an assortment of wood lengths with which to experiment.

After noon Zackuth grew restless and went off, to come back with a deer, visibly proud of his hunting skill. Craike saw bowstrings where the others saw meat and hide for the refashioning of foot wear. For the rest of the day they worked with a will. It was Takya, who had the skill necessary for the feathering of the arrows after Zackuth netted two black river birds.

Four days later the tower community had taken on the aspect of a real stronghold. Many of the fallen stones were back in the walls. The two upper rooms of the tower had been explored, and a vast collection of ancient nests had been swept out. Takya chose the topmost one for her own abode and, aided by her convalescing charge, the boy Nickus, had carried armloads of sweet-scented grass up for both carpeting and bedding. She did not appear to be inconvenienced by the bats that still entered at dawn to chitter out again at dusk. And she crooned a welcome to the snowy owl that refused to be dislodged from a favorite roost in the very darkest corner of the roof.

River travel had ceased. There were no new offerings on the rock. But Jorik and Zackuth hunted. And Craike tended the smoking fires which cured the extra meat against coming need, while he worked on the bows. Shortly they had three finished and practiced along the terrace, using blunt arrows.

Jorik had a true marksman's eye and took to the new weapon quickly, as did Nickus. But Zackuth was more clumsy, and Craike's stiff leg bothered him. Takya was easily the best shot when she would consent to try. But while agreeing it was an excellent weapon, she preferred her own type of warfare and would sit on the wall, braiding and rebraiding her hair with flying fingers, to watch their shooting at marks and applaud or jeer lightly at the results.

However, their respite was short. Craike had the first warning of trouble. He awoke from a dream in which he had been back in the desert panting ahead of the mob. Awoke, only to discover that some malign influence filled the tower. There was a compulsion on him to get out, to flee into the forest.

He tested the silences about him tentatively. The oppression which had been in the ancient fort at his first coming had not returned, that was not it. But what?

Someone moved restlessly in the dark.

"Lord Ka-rak?" Nickus' voice was low and hoarse, as if he struggled to keep it under control.

"What is it?"

"There is trouble—"

A bulk which could only belong to Jorik heaved up black against the faint light of the doorway.

"The hunt is up," he observed. "They move to shake us out of here like rats out of a nest."

"They did this before with you?" asked the Esper.

Jorik snorted. "Yes. It is their favorite move to battle. They would give us such a horror of our tower that we will burst forth and scatter. Then they can cut us down as they wish."

But Craike could not isolate any thought beam carrying that night terror. It seeped from the walls about them. He sent probes unsuccessfully. There was the pad of feet on the stairs, and then he heard Takya call:

"Build up the fire, foolish ones. They may discover that they do not deal with those who know nothing of them."

Flame blossomed from the coals to light a circle of sober faces. Zackuth caressed the spear lying across his knees, but Nickus and Jorik had eyes only for the witch maid as she knelt by the fire, laying out some bundles of dried leaf and fern. Her thoughts reached Craike.

"We must move or these undefended ones will be drawn out from here as nut meats are picked free from the shell. Give me of your power—in this matter I must be the leader."

Though he resented anew her calm assumption of authority, Craike also recognized in it truth. But he shrank from the task she demanded of him. To have no control over his own Esper arts, to allow her to use them to feed hers—it was a violation of a kind, the very thing he had so feared in his own world that he had been willing to kill himself to escape it. Yet now she asked it of him as one who had the right!

"Forced surrender is truly evil—but given freely in our defense this is different." Her thoughts swiftly answered his wave of repulsion.

The command to flee the tower was growing stronger. Nickus got to his feet as if dragged up. Suddenly Zackuth made for the door, only to have Jorik reach forth a long arm to trip him.

"You see," Takya urged, "they are already half under the spell. Soon we shall not be able to hold them, either by mind or body. And then they shall be wholly lost—for ranked against us now is the high power of the Black Hoods."

Craike watched the scuffle on the floor and then, still reluctant and inwardly shrinking, he limped around the fire to her side, lying down at her gesture. She threw on the fire two of her bundles of fern, and a thick, sweet smoke curled out to engulf them. Nickus coughed, put his hands uncertainly to his head and slumped, curling up as a tired child in deep slumber. And the struggle between Jorik and his man subsided as the fumes reached them.

Takya's hand was cool as it slipped beneath Craike's jerkin, resting over his heart. She was crooning some queer chant, and, though he fought to hold mind contact, there was a veil between them as tangible to his inner senses as the fern smoke was to his outer ones. For one wild second or two he seemed to see the tower room through her eyes instead of his own, and then the room was gone. He sped bodiless across the night world, casting forth as a hound on the trail.

All that had been solid in his normal sight was now without meaning. But he was able to see the dark cloud of pressure closing in on the tower and trace that back to its source, racing along the slender thread of its spinners.

There was another fire, and about it four of the Black Hoods. Here, too, was scented smoke to free minds from bodies. The essence which was Craike prowled about that fire, counting guardsmen who lay in slumber.

With an effort of will which drew heavily upon his strength, he concentrated on the staff which lay before the leader of the company. Setting upon it his own commands.

It flipped up into the air, even as its master roused and clutched at it, falling into the fire. There was a flash of blue light, a sound which Craike felt rather than heard. The Hooded Ones were on their feet as their master stared straight across the flames to Craike's disembodied self. His was not an evil face, rather did it hold elements of nobility. But the eyes were pitiless, and Craike knew that now it was not only war to the death between them, but war beyond death itself. The Esper sensed that this was the first time that other had known of his existence, had been able to consider him as a factor in the tangled game.

There was a flash of lightning knowledge of each other, and then Craike was again in the dark. He heard once more Takya's crooning, was conscious of her touch resting above the slow, pulsating beat of his heart.

"That was well done," her thought welcomed him. "Now they must meet us face to face in battle."

"They will come," He accepted the dire promise that Black Hood had made.

"They will come, but now we are more equal. And there is not the Rod of Power to fear."

Craike tried to sit up and discovered that the weakness born of his wounds was nothing to that which now held him.